June 2006

![]()

AutomatedBuildings.com

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

(Click Message to Learn More)

June 2006 |

[an error occurred while processing this directive] |

|

Stop Trying to Solve Business Problems with a Control System |

|

In last month’s article, “How Can a Building be Intelligent if it has Nothing to Say?” we discussed the importance of information in making a building intelligent. Some of the points of that article include:

Business value comes from information, not technology. Technology’s role is to facilitate information access.

Productivity gains come from information/data, not IP or browser-based interfaces.

Old data can provide tremendous new value.

Access to any data is not the same as having all the data, as there’s a difference between controls system-based buildings and information-based buildings.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[an error occurred while processing this directive] |

This last bullet is the subject of this month’s article.

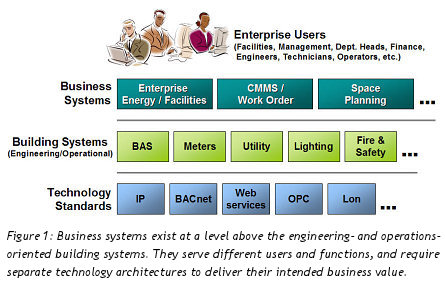

Building systems (building automation systems, metering systems, etc.) and business-oriented IT applications have different architectures and data needs. A control system’s representation of a building and an IT representation of that same building, are very different. Neither one can do the other’s job, nor should they try.

What does all this mean to the average (or above average) facilities leader? It boils down to what you can and can’t accomplish. What information you can extract from the data? How quickly? What knowledge can be gained, and by whom? Ultimately, this is a building block to transform facilities operations from a building management organization to a service-oriented business.

Any versus All

We hear it frequently—especially with newer, open control systems—you can access any point in the system or trend any point in the system. Actually, that’s been mostly true for a while. Most DDC systems can view or trend any point, even those systems we now refer to as legacy. That works OK for control systems, but falls totally flat when it comes to building information systems.

Compare “access to any data” with possessing all the data, all the time, for every point. The historical record of how systems operate, how they interact, how they respond to various external conditions such as weather and occupancy, creates the foundation for a facilities business system.

Think about other business systems. What would a sales information system be like without all the sales data? Could you run a retail business with only today’s sales data? How about historical data, but from only two percent of the stores? These fit the “access to any point” or “trend any point” information model, but it’s absurd to imagine running a $50 million retail business this way. So why run a $50 million facilities operation with “any” data?

In contrast, look at a sales system with all the data. You can trend and analyze sales in any dimension, look at correlations with weather, see how different stores perform compared to each other or to industry benchmarks, identify the impact of exemplary (or poor) performance. In short, you can make informed business decisions and ensure that stores are run the way you intended. Now, change “sales” to “operations” and “stores” to “buildings,” and the same is true for running a facilities business.

Separate Representations, Separate Data

Now that we’ve established the business need for all the data, does that mean you should turn on trending for every point in your building systems? No. Odds are that will bring the control function to its knees. Instead, what is needed is an information system that extracts data from the control system into a separate data warehouse—an IT representation of the building. By doing so you take the burden for data collection and data management off the control system, which isn’t designed for it in the first place, and create the basis for a facilities business system.

This approach is necessary even for the few control and metering systems that are capable of logging all the data into their own database. Metering systems are used to trending a lot of meter points, but can you afford to meter everything—every fan, pump, cooling coil, etc.—not a chance. But it’s not just a cost issue. There are several other advantages to separately collecting data for business applications:

Many control systems only keep data for a few days or a few months. This way you can keep the data forever, creating a historical record of how your facilities operated.

All prior data is available, no matter when you need it or what you need it for.

You can combine and correlate data from many different building systems, or even other business operational systems, for analysis.

The data warehouse architecture is not tied to the needs of the building systems, enabling a different set of business applications.

An unlimited amount of modeling and analysis is possible using actual past operational data to improve future operations, designs, and financial performance.

The data becomes accessible by a wide variety of users across the enterprise and external contractors, instead of limited to control system users, increasing the knowledge base of the entire facilities organization.

Using IT to Add Business Value

The advantages of a separate building representation, collected into its own data warehouse are examples of how an information technology (IT) system adds business value. They are built around the business needs of their users, supporting the way you run your business, but also facilitating the transformation from service delivery to operating as a multi-million dollar business.

Don’t assume the word “business” only refers to finances. Managing a facilities operations business requires tackling many issues—service-level agreements (explicit or implied) for comfort, health and safety, utilities services, building maintenance, and several hundred employees to manage. There are new construction projects, renovations, and qualitative issues such as accountability and credibility. And of course, there is the financial side of managing utility costs, budget cycles, capital requests, etc.

IT

systems can completely change how you approach every one of these business

challenges. The data collection discussed above is just the first step—a

critical step, but only the first of many. The IT system must organize data to

make it easy for end-users to extract actionable information. The organization

must be flexible to enable many different views, as diverse users have unique

needs. These organizational requirements inform the data representation, which

conversely allows or limits the flexibility of information organization and

presentation.

IT

systems can completely change how you approach every one of these business

challenges. The data collection discussed above is just the first step—a

critical step, but only the first of many. The IT system must organize data to

make it easy for end-users to extract actionable information. The organization

must be flexible to enable many different views, as diverse users have unique

needs. These organizational requirements inform the data representation, which

conversely allows or limits the flexibility of information organization and

presentation.

In the end, the business value from an IT-based building system comes from the ability to make better decisions, increase productivity, improve customer service, and other business improvements. The IT representation needs to translate these high-level benefits into detailed implementation decisions. For example, how data trees are constructed, what reports exist (and what data feeds them), the level of interactivity for ad hoc analysis, the ability to layer calculations on top of raw data, are all defined by varying users and uses of the information system.

The information to transform your facilities operation into a business is not possible with today’s control systems, metering systems, or other engineering-level applications. This is why you need to collect all the operational data separately—to build a business-level system (see Figure 1) capable of delivering entirely new levels of value.

Real-World Examples

Enough with the theory. Let’s look at some typical examples where the world changes if you have an information system in place.

[an error occurred while processing this directive] Hot/cold call: You get a hot or cold call. What happens? In most cases the technician that responds will check the current conditions, adjust a thermostat or override a setpoint, and that’s about it. If the room has habitual problems, perhaps there are a few trend logs running, but what data is available?

An information system provides operational details for every room (or zone) in the building. The technician not only sees current conditions, but also knows how long the space has been uncomfortable, how well the air handler is running, how the terminal box is operating, cooling and reheat valve behavior, etc. In most cases, it only takes five minutes to determine the real cause of the comfort problem so that the proper correction is made the first time.

Taken a step further, facilities has the information to show its customers what happened. Historical data showing the space becoming uncomfortable, the extent of which is measured in a comfort index (calculated from the captured data) that non-engineers can easily understand. The information is there to show when the call was logged, the corrective action taken, and exactly how long it took to become comfortable again.

The IT system helps the business of meeting the comfort obligation, providing fast and accurate customer service, and communicating with the customer in a way that they understand.

Business metrics: Facilities leaders and executives have entirely different information needs. They need to understand how the business is running—how current operations stack up against last month, last year, industry standards, and organizational goals. Utility bills are a terrible way to manage the business. Too few data points that are far removed from the time they account for.

A big advantage of separating the collected operational data from the control systems is the additional processing that IT systems can perform. Take a supply fan, for example. Most control systems can tell you if the fan is on or off, and the percent of full-load amps. That is all you need to calculate the kWh for the fan. The manufacturer’s specifications will supply horsepower, motor efficiency, and any other necessary parameters. Add utility rate information and you can report the cost in dollars/hour at any point in time.

Similar capabilities exist to measure the energy consumption of pumps, heating and cooling units, exhaust fans, or any other mechanical systems. These are the building blocks that most facilities executives only dream about. With them you can produce reports that show the metrics of your choice for the building, broken down by air handler and each piece of equipment, or broken down by floor, zone, or room. Metrics that normalize across multiple buildings, such as MBtu/SqFt become simple. Accounting for weather is similarly easy. The information is there to see what’s running well and what isn’t, what’s improving and what’s not.

The ability to set and meet concrete goals, measure successes and document issues, and prioritize work are just some of the real-world advantages a true information system provides that control systems cannot.

Growing staff knowledge: Some facilities organizations perceive adding an information system as yet another thing to do. Who has time to look at the information? The short answer—almost everyone.

A major goal of IT systems is to deliver the right information to the right users, and do it fast. Instead of spending four hours in spreadsheet hell, you can spend 40 seconds pulling together the information you need. You can, that is, if the underlying data is complete and the system was designed to meet users’ requirements. You’re not likely to train 100+ users to use the control system. Even if that were easy, you wouldn’t want to. IT systems are designed to handle hundreds, even thousands, of different users’ information needs.

When more people start using information to understand how the buildings and systems they work with daily actually function, good things happen. Issues are caught before they become problems. Communications improve. Learning happens. Staff can see the impact of their work. The total knowledge base of facilities team rises. Growing the staff’s knowledge is good business as tomorrow’s challenges will be greater than today’s.

[an error occurred while processing this directive] The Bottom Line

Building control systems exist at the engineering or

operational level. They are not designed as business systems, nor should they

try to be as their primary function is of critical importance. The control

system representation of a building is different from an IT representation at

both the technical and end-user level.

IT systems, when done properly, have changed the way businesses function. Every

other function in a company/institution has changed over the past 25 years due

to the availability of information—finance, administration, sales, customer

service, marketing, manufacturing, R&D, distribution, you name it.

Only facilities operations has yet to take this step. It’s a step that requires a business mentality and a new approach in both technology and management.

About the Authors

Bill Gnerre is the CEO and cofounder of IDS. With over 20 years of information technology entrepreneurial experience, he has an exemplary record of bringing enterprise software applications to market and dealing with user adoption of new technology. In addition to facilities operations and enterprise energy management, his background includes experience with CAD/CAM, engineering document management, PDA data collection, and other customized enterprise applications. Bill provides leadership and strategy for IDS and works closely with clients to ensure their success. He can be reached at bill@intdatsys.com.

Kevin Fuller is responsible for marketing and product development for IDS. He brings over 20 years of technical and marketing experience in database, data warehouse, OLAP, and enterprise applications to his role as executive vice president. Kevin has a strong appreciation of how businesses use data to their advantage, and focuses on how to apply technology to solve real business problems. He can be reached at kevin@intdatsys.com.

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

[Click Banner To Learn More]

[Home Page] [The Automator] [About] [Subscribe ] [Contact Us]