TLDR: The article examines the increasing concerns among Americans regarding the pervasive role of AI in their lives, as evidenced by a 2023 Pew Research Center survey showing a marked rise in apprehension. It delves into the psychological and societal factors that shape attitudes towards AI and the mechanisms that foster or alleviate anxiety.

Recently the personal care brand, Dove (Unilever) released a new ad celebrating the 20th anniversary of their famous Campaign for Real Beauty that’s getting a lot of attention. The company isn’t sheepish about its stand against the marketing of “fake” beauty products, photoshopped fashion models, and social media images that market impossible beauty standards to young girls. With this latest ad, entitled “The Code”, Dove has doubled down its efforts and taken on the explosive market of AI-generated images, which it pledges to never use to “create or distort women’s images”.

The ad is flooding social media platforms, giving fresh oxygen and awareness to the hotly debated topics of social media impacts on young people, impossible standards of beauty, and the rising depression and anxiety levels among teenage girls. The ad also throws down the marketing gauntlet to firms and companies around the world, implicitly asking, “Will you follow “The Code” of conduct we’re committing to?”

However, the ad’s strong message and stance against AI comes on the heels of a recent spike in concern among Americans around AI and its influence on our daily lives. The fear of AI, or algorithmophobia, is a topic I covered in an earlier piece where I make the argument that our industry’s marketing strategy needs to better understand the causes of algorithmophobia so as to adapt its messaging to overcome common consumer fears.

In the article, I explored how popular culture often polarizes our view of AI, depicting it as either entirely benevolent or entirely malevolent. I argued that such extreme views could heighten anxiety about adopting new technologies. In this piece, however, I aim to delve deeper into the psychological factors that shape our attitudes towards technology and to examine the recent surge in concerns and their underlying causes.

In doing so, I do not wish to dismiss legitimate concerns about AI or AI-generated content and its potential impact on body image and mental health. There are valid reasons for caution, given AI’s unpredictable effects and recent emergence. Instead, my focus is on exploring the deeper-rooted anxieties that arise with the advent of technologies like AI—fears about the very concept of artificial intelligence and the apprehensions that typically accompany such disruptive innovations. Addressing these fears is crucial for us to fully leverage the benefits that AI offers.

Concerns Around AI Among Americans is Rising Sharply

A recent 2023 Pew Research Center Survey looked at how Americans felt about the role of artificial intelligence in their daily lives. The survey showed a sharp increase from the two previous years. When asked how the increased use of AI in daily life made them feel, 52% of respondents said they were more concerned than excited. In 2022, that number was 38%, and in 2021 it was 37%. So, what’s contributing to this bump in concern?

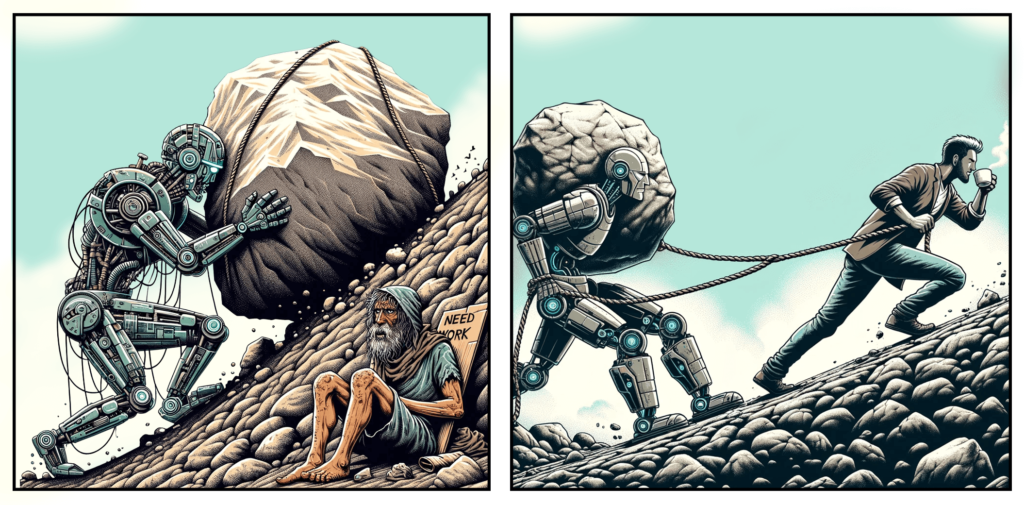

One factor is the explosive growth in AI’s development and deployment, along with the resulting increase in media coverage and debate. We hear, see, and read about AI everywhere now. The public’s awareness is rising and likely outpacing a fuller understanding of AI.

In fact, Pew reports that while most Americans (90%) are aware of AI, the majority are limited in their ability to identify many common uses of the tech (e.g. email spam detection or music playlist recommendations). Awareness without understanding promotes anxiety. It’s functional. Our ancestors (those who survived to procreate) tended to focus more on a general awareness of potential threats than our kin who felt compelled to gain a true understanding of what was making noises in the bushes over there!

To that point, the survey showed that education plays a role in attitudes. Adults with a college or postgraduate degree are more likely to be familiar with AI than those with less education. Also, Americans with higher levels of education tend to be more positive towards AI’s impact on their lives.

However, it’s also important to note that more educated Americans are more likely to work with AI. In 2022, 19% of American workers were in jobs that are most exposed to AI. Those jobs tend to be in higher-paying fields where higher education was beneficial. Working with AI on a practical level helps explain more positive attitudes in this population. Education and experience often allay fears.

The Function of the “Human Element” in our Attitudes

One of the more interesting take-aways from the Pew surveys was the shifting levels of trust in AI when it came to the absence or existence of the “human element”— those parts we tend to value (creativity, empathy, analytical thinking) and those we tend to avoid (bias, destructive impulses, impulsiveness).

However, it’s this ambivalence to the human side of AI that provides more valuable insights into how we form our attitudes. Consider these Pew Survey findings on health care:

- 65% of Americans say they would want AI to be used in their own skin cancer screening.

- 67% say they would not want AI to help determine the amount of pain meds they get.

Now, consider how U.S. teens responded to a Pew survey asking them about using ChatGPT for schoolwork:

- 39% said it was “acceptable” to use ChatGPT to solve math problems.

- Only 20% said it was “acceptable” to use ChatGPT to write essays.

What explains the apparent contradiction here? What’s the difference between skin cancer screening and pain med management? Why did twice as many respondents find it acceptable to use AI to solve math problems but not write essays?

Part of the answer is we assign varying levels of subjectivity or “human-ness” to different tasks (even though humans do them all). In other words, it’s more “human” to compose an essay because writing is about expressing yourself. Math is about following strict rules. The same attitude usually applies even when you’re tasked with writing an objective, unbiased, and factual piece like a news article. However, aren’t these the same strategies you need to solve math problems?

To diagnose skin cancer successfully, it helps to be experienced, objective, and unbiased. AI skin cancer detection systems are trained on thousands of high-res images of skin lesions. These systems can remember and compare them all, dispassionately and efficiently. No ambiguity. No corrective lenses. No hangover from last night’s bar hopping.

On the other hand, accurately gauging someone’s pain level requires a person who feels pain, a human who’s shared the experience of pain, who has empathy and compassion. It’s likely it’s this lack of human connection that engenders distrust in AI on this issue.

Our Attitudes are Contextual

It’s also important to recognize our attitudes align with the aim of our motives. While most of us are capable of compassion and empathy, these faculties also make us easy to manipulate. In most instances, it’s easier to bullshit your way through a book report than a calculus problem. Also, most people would have more success convincing a human doctor to over-prescribe pain meds than an AI physician. If we need moral nuance or ethical wiggle room, we distrust AI to accept such gray areas. I may be able to convince you that 2 + 2 = 5, but I can’t “convince” my calculator.

What these surveys show is that our attitudes and trust in AI are highly contextual. They change based on the stakes of potential outcomes and the need for objectivity or subjectivity (perceived or actual). If the potential negative outcomes are low (a robot cleaning our house), we tend to trust more. However, we wouldn’t want a robot to make life-altering decisions about our health, unless that decision required high levels of objectivity and unbiased judgment…but only to a point. Thus, this back-and-forth “dance” with AI is our ambivalence at work.

Subjectivity and objectivity are both part of the human experience, yet we prioritize subjective faculties like compassion, empathy, trust, expression, and creativity as “truly human” qualities. The crux of the issue is that, while these aspects of ourselves are indeed some of our best features, they are also the source of our distrust of ourselves and, by extension, AI. Because we are compassionate, we can be manipulated. Because we are emotional, we can be biased. Because we are trusting, we can be deceived. This double-edged sword pierces the heart of our shifting attitudes towards AI.

Mechanisms That Shift Attitudes Towards Technology

The Pew Surveys show American’s trust of AI runs along a spectrum. Just as the temperature in a building is regulated by a thermostat, our individual and collective trust in AI is influenced by an array of ‘control mechanisms’—such as our education levels, occupations, media portrayals—that continuously modulate our comfort levels and perceptions of safety with the technology. So, what else adjusts the thermostat? I asked clinical psychologist Dr. Caleb Lack to help me identify some common factors that could influence public sentiment on AI.

Habituation

One common mechanism to calm nerves around technology is the simple passage of time. All big technologies—like automobiles, television, and the internet—follow a similar journey from resistance to full adoption. Given enough time, any new tech will go from being “magical” or “threatening” to being commonplace.

“I think what often happens with tech is people habituate to it,” explains Lack. “As with any new technology, you just become used to it. Rule changes in sports are a good example. People will often complain about them at first. Two seasons later, no one is talking about it. It’s how it is now, so that’s how it’s always been. Humans have very short memories and most of us don’t reflect much on the past.”

Social Media & Mental Health

We often hear mental health and technology experts sounding the alarm about the negative effects of smartphones and social media. And with good reason. Studies continue to show the negative effects of smartphones, social media, and algorithms on our mental health, especially in adolescents.

One 2018 study showed participants who limited their social media usage reported reductions in loneliness and depression compared to those who didn’t (Hunt, Melissa G., et al). Another found significant increases in depression, suicide rates, and suicidal ideation among American adolescents between 2010 and 2015, a period that coincides with increased smartphone and social media use (Twenge, Jean M., et al).

Few of us have failed to notice the irony that “social” media seems to be making us feel more alone. Many are asking will AI super charge social media, create something that further alienates and damages mental wellbeing of young people. The Dove ad is a product and a reflection of this collective anxiety.

The “Black Box” of Technology

The term “black box” refers to any kind of system or device where the inputs and outputs are visible, but the processes or operations inside are hidden from the user. For most of us, the world is one big black box, technologically speaking.

“Technology of all kinds has become impenetrable for most of the population,” says Lack. “I think that’s where we’re seeing a lot of concern around AI. To someone completely unfamiliar, DALL·E or ChatGPT look like magic. It’s completely incomprehensible. But, then again, how many of those people know how their car works, or their phone, or the internet even. We eventually habituate and just accept them as normal.”

Even if we normalize new technology and forget our previous concerns, an opaque world is still a strange one, and we don’t do well with strange for extended periods of time. We need resolution. We either find out what’s really making noise in the bushes over there, or we run away. Either way, we’re satisfied with our newly acquired knowledge of the real squirl we discovered or the imagined snake we avoided. Yet, how do we run away from an inscrutable technology that’s increasingly integral to our lives? Enter anxiety…

Skills Specialization

The jobs and tasks we do are getting more and more specialized. It’s a consequence of technology itself. We can’t know everything obviously, and specialization can increase efficiency, bolster innovation, and raise wages for workers. However, these benefits have social costs, according to Lack, who offers an insightful perspective on the connection between specialization and social isolation:

“Our knowledge and skills have become so siloed we don’t know what anyone else is doing. You only know your own skills and knowledge. These knowledge silos are keeping us from connecting with others. At the same time, we’ve also become more physically disconnected from people mostly because of technology. The resulting social isolation is a major source of anxiety for humans. If you socially isolate someone, the same areas of their brain become active as if you’re actively torturing them,” he cautions.

The Great Replacement Theory

As we’ve seen, algorithmophobia draws on other common parts of general tech phobia. However, it does seem to carry a unique feature not seen with other technologies. Lack refers to the feature as the “fear of supplantation” or the idea that AI could replace humanity altogether. The notion goes well beyond just taking jobs, but making humanity obsolete, a vestigial species.

“When cars came along,” he explains, “people weren’t worried Model T’s would become sentient, take over, and kill everyone. Today, that fear does exist. So, it’s not just worries around the safety of self-driving cars. It’s about safety, and the fear that humanity may not survive, that life will become Christine meets Terminator.”

Although supplantation is a unique fear with respect to technology and AI, it’s an anxiety as old as humanity itself. “We see fear of supplantation in racist tropes also,” Lack explains. “They’re coming to take my job. They’re coming to marry into my family. They’re coming to replace me. Humans are really good at creating Us vs Them mentalities.”

“Artificial Intelligence” as Competitor to Humanity

Previously, I’ve argued that how we market “artificial intelligence” is important to how consumers will respond to it. To quell anxieties in consumers, I’ve called for “Dehumanizing” AI, by minimizing its human side and “promoting it as a tool first and foremost.” There is a balance to be struck. Imbuing AI with too much “humanity” risks stoking fears of replacement. Too little may diminish the advantages of technology to automate our thinking.

Lack agrees that what we call AI has important psychological implications. In fact, he argues that the moniker “artificial intelligence” creates an antagonistic relationship by making it a direct competitor for resources.

“You’re setting AI up essentially as another species,” he explains. “Competition over resources has been one of the biggest drivers of conflict for our species. We have a hard enough time getting along with even slightly different members of our own.”

Conclusion

As AI continues to permeate every facet of our lives, it is essential to understand and address the multifaceted anxieties it generates among the public. The 2023 Pew Research Center survey serves as a bellwether for rising concerns, indicating a need for greater education and transparency about AI’s role and capabilities. By exploring the psychological underpinnings and societal impacts of AI integration, we can better navigate the complex dynamics of technology adoption.

Efforts to demystify AI through clearer communication, coupled with practical exposure, can alleviate fears and foster a more informed and balanced perspective. Ultimately, addressing the human element in technological development and ensuring ethical standards in AI applications will be pivotal in harmonizing our relationship with these advanced systems, ensuring they enhance rather than detract from societal well-being.

Works Cited

Twenge, Jean M., et al. “Increases in Depressive Symptoms, Suicide-Related Outcomes, and Suicide Rates Among U.S. Adolescents After 2010 and Links to Increased New Media Screen Time.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, vol. 127, no. 1, 2018, pp. 6-17. DOI:10.1037/abn0000336.

Hunt, Melissa G., et al. “No More FOMO: Limiting Social Media Decreases Loneliness and Depression.” Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, vol. 37, no. 10, 2018, pp. 751-768. DOI:10.1521/jscp.2018.37.10.751.

Pew Research Center Articles

What the data says about Americans’ views of artificial intelligence

60% of Americans Would Be Uncomfortable With Provider Relying on AI in Their Own Health Care

Which U.S. Workers Are More Exposed to AI on Their Jobs?

Public Awareness of Artificial Intelligence in Everyday Activities

Growing public concern about the role of artificial intelligence in daily life

Caleb W. Lack, Ph.D. is a Professor of Psychology at the University of Central Oklahoma.