May 2009

![]()

AutomatedBuildings.com

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

(Click Message to Learn More)

May 2009 |

[an error occurred while processing this directive] |

|

|

|

With the current push to reduce energy consumption in commercial buildings energy service companies (ESCOs) are seeing rapid growth. According to a report issued by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory ESCO industry revenues rebounded with growth of 20% per year in 2004 to 2006.1 This is up significantly from growth rates between 2000 and 2004, which averaged only 3%.2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[an error occurred while processing this directive] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[an error occurred while processing this directive] |

ESCO industry revenues from energy efficiency

accounted for about $2.5 billion in 2006.3 A sizeable number to be

sure, but is this enough to impact how buildings are really using energy? If we

assume that those making decisions to purchase energy services used the typical

industry return on investment criteria of 14 to 33% (3 to 7 year simple payback)

we can estimate that the energy savings generated from this investment is in the

ballpark of $300 to $800 million. This is less than 0.5% of the $166.7 billion

spent on energy in U.S. commercial buildings in 2006.4

Here’s the problem. Net of all conservation efforts, the demand for energy in

the U.S. is still growing at a rate of 2 to 3% per year. Growth of 3% on a base

of nearly $170 billion is about 10 times the annual savings generated by ESCO

activity. Even if the ESCO industry were to continue to grow at 20% per year, it

would be nearly 50 years before the annual savings were enough to completely

offset the increase in demand.

I don’t think that’s good enough. The ESCO industry, as it exists today, cannot

get the job done. Energy services need to be reinvented.

Who Plays Today?

The vast majority of the energy services work is done by a small number of

national players. Only 46 energy service companies were identified in the

Lawrence Berkeley market study. Over ¾ of the total revenue is generated by 10

companies, and the trend toward industry consolidation continues even today.5

The fact that a few large companies dominate the market is not inherently bad –

in fact economies of scale offer some great advantages that will be discussed

later. The larger issue stems from the methods used by these companies, and

ultimately the type of projects that get done.

What Projects Do Get Done?

In 2006, over 80% of ESCO industry revenue was from institutional facilities

– 22% in the federal market, 58% in state/local government, universities,

schools, and hospitals market, and 2% among public housing.6 That

leaves only 18% for private sector investment. Two reasons for this:

1. The propensity for Energy Saving Performance Contracts (ESPC) in this market. The net effect of the use of these more sophisticated financial instruments creates lower return on investment requirements for the public sector that what is generally accepted in the private sector. This allows more projects to move forward with longer payback periods. [Note: This could play havoc with the savings assumptions made above, making the 50-year assumption for turning around the growth in consumption stretch out even longer.]

2. The project size from this sector is generally larger. Government, universities, schools, and hospitals have long been the drivers for performance contracts. Most projects undertaken by the major ESCOs are at least $1 million in size, and are conducted in buildings that are greater than 250,000 square feet.

The Methods Drive the Madness

When most of the project work is done in large, complex facilities and the

projects are structured as ESPCs with significant financial risk for the ESCO,

it’s no wonder that the energy auditing methods employed are very rigorous.

Labor-intensive, engineering-intensive methods are used to analyze the

opportunity for energy savings in very complex projects. Those methods drive the

cost of the analysis up so high that only the largest projects can support it.

Those are the types of projects that are always done, so the industry trains

itself only in the methods to support them. It becomes a spiral that can’t be

escaped. Meanwhile, a huge segment of the market goes unserved.

Building

Demographics

Building

Demographics

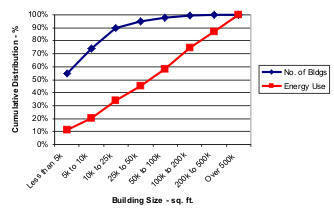

Of the 4.6 million commercial buildings in the U.S., less than 1% are

greater than 200,000 square feet. Those buildings consume about 25% of the total

energy used.7 This is a significant percentage to be sure, and it

makes obvious sense to start with the largest buildings that consume the most

energy per building, but we can’t get to where we all want to go by ignoring the

energy savings opportunities that exist in the base of smaller buildings that

consumes 75% of all the energy used in commercial buildings.

What’s Needed – Reinvention of a Scaleable Business Model for Energy Services

In order to reinvent the business model for energy services in a way that

can effectively attack the energy savings opportunity that exists in facilities

under 200,000 square feet three critical factors are needed:

1. New Channels to Deliver Energy Services

In order to effectively serve millions of buildings that aren’t being served today, new channels to deliver energy services will be required. This can most effectively be accomplished not by trying to expand the service footprint of existing energy service providers into those buildings, but by looking at providers that are already performing services in those buildings and expanding the scope of those services to now include energy.

Channels exist today that effectively deliver a wide range of services to these millions of buildings – facilities management services, mechanical HVAC services, electrical services, janitorial services – all have feet on the street to do the jobs they do today. The problem is those feet are walking right past opportunities to save significant energy in nearly every building they serve today.2. New Methods to Deliver Energy Services

The methods used to quantify savings and determine energy conservation measures need to be reinvented. Labor content must be managed. In smaller buildings the total energy savings potential is smaller. The ultimate cost of the project, and the upfront cost to prepare the proposal must be smaller in roughly the same proportion in order for the model to scale. New methods are emerging that bring automation into the tasks of data collection, analysis, and reporting reduces the amount of labor required to perform an audit of energy performance in a building.

A second challenge is staffing enough qualified personnel in order to handle the increased volume of smaller projects. It will be necessary to use a process that requires less senior engineering personnel, and ideally builds “bench strength” of more junior engineers or technicians as they gain important field experience. The focus on automation of the data capture process and the use of expert systems to help diagnose building performance and uncover potential savings is a critical aspect in reducing the level of expertise required to economically accomplish the initial assessment of energy performance, and making more strategically effective use of senior engineering resources.3. New Programs to Promote Energy Services

Emerging markets need catalysts. Energy services delivered to a new segment of buildings by new channels is no different. Obviously, some significant catalysts are already in play. Rising energy prices and the strong push for companies to be green or sustainable are two examples. Carbon taxes or cap and trade systems that in effect, create further increases in the cost of energy is another. Utility conservation programs have worked very well and need to be expanded and refocused on these new methods and projects. Finally, service providers themselves need sales and marketing programs that can effectively communicate the benefits of their services in new ways to support a low cost / high volume model of delivering energy services.

What’s unique about the energy efficiency and conservation space is that you will meet people with very disparate motivations along the same road to the same place. Whether climate change is the driver, or national security, or the economic benefits is the key – we all are trying to get to the same place – using less energy. The current ESCO model is making an impact by slowing the rate of growth of energy use in certain building segments. To actually turn the tide and reduce the total amount of energy used in commercial buildings will require reinvention. There’s no time like the present to start.

[1]

Hopper, Nichole, Charles Goldman, Donald Gilligan, Terry Singer, Dave Birr.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, LBNL-62679, A Survey of the U.S. ESCO

Industry: Market Growth and Development from 2000 to 2006, May 2007.

[2] Ibid

[3]

Ibid

[4]

U.S. Department of Energy, Building Energy Data Book.

[5]

Hopper, Nichole, Charles Goldman, Donald Gilligan, Terry Singer, Dave Birr.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, LBNL-62679, A Survey of the U.S. ESCO

Industry: Market Growth and Development from 2000 to 2006, May 2007.

[6]

Ibid

[7]

Energy Information Administration, Commercial Building Energy Consumption

Survey (CBECS), 2003.

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

[Click Banner To Learn More]

[Home Page] [The Automator] [About] [Subscribe ] [Contact Us]