December 2005

![]()

AutomatedBuildings.com

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

(Click Message to Learn More)

December 2005 |

[an error occurred while processing this directive] |

|

|

Scott Howell, |

A security robot lounges in the first-floor lobby of a research laboratory, its on-board computer sleeping to preserve batter power. It's 4:00 a.m.

Suddenly, the building’s access control system detects a propped door. One of the laboratory’s side doors has remained open too long following an authorized card presentation.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[an error occurred while processing this directive] |

As usual, the access control software triggers an alarm in the off-site security control center, advising the officer on duty. Security personnel will monitor what happens next, ready to respond if necessary. Chances are, however, that several technological systems in the building will work out the problem on their own.

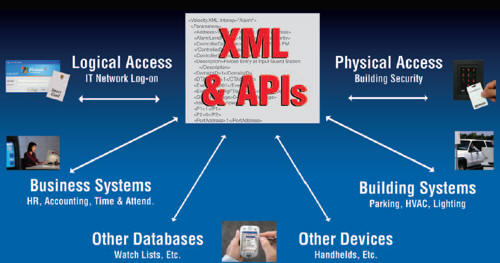

XML Opens the Door

All night long, the access control system has been broadcasting security

system events to other systems that are authorized to listen. The data format is

XML—eXtensible Markup Language—the de facto standard for machine-to-machine

communication.

The XML data, written in short bursts of plain English, is so simple that even the non-technical professional will understand it right off the bat.

<SecuritySystemMessage>

<EventType>Alarm</EventType>

<EventSpecifics>DoorOpenTooLong</EventSpecifics>

<Location>LabSideDoor</Location>

</SecuritySystemMessage>

As much as 99.9% of the data bouncing around among the different systems is ignored. Authorized users and vehicles coming and going, for instance, raise no red flag. But when the XML listener spots the phrase in the security system’s XML stream about the propped lab door, it triggers a series of actions in other systems.

The building’s lighting control system responds by turning on the lights in the corridor adjacent to the propped door. The CCTV system activates a preset program to pan, tilt and zoom a nearby camera onto the propped door.

In the lobby, the robotic security guard hears about the alarm condition over the wireless communications net work and matches the alarm location to the floor plan stored in its memory. It moves unassisted from the lobby to the lab’s side door, where it finds two people: an authorized cardholder and someone who followed him through the door—a piggybacker—just inside a door that has been propped open with a box. All of this happens within a few moments of the alarm.

At the scene, a camera in the robot focuses on the two people. From the remote security center, the security officer talks to them, live, over the robot’s two-way radio. Turns out they are lab technicians who have come to work early to check on an experiment. The security officer suggests the piggybacker hold his photo ID up to the robot’s camera lens and present his access card to the proximity reader mounted on the robot. The robot sends the card data to the access control system, which verifies current employment status and area authorization. The alarm condition is cancelled. Interoperability ensures the lab is secure and even negates the need for a physical response.

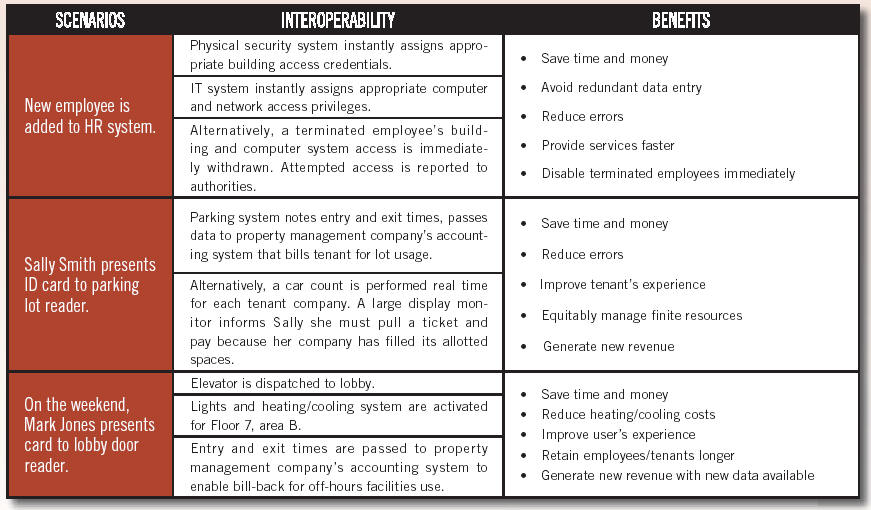

While this scenario consolidates a number of examples of interoperability, nothing about it is futuristic. Each is currently being implemented in real-world applications.

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

CCTV from the Access Control System

At the Orlando Sanford International Airport in Florida, the Velocity access

control system from Hirsch Electronics will soon begin to interoperate with a

CCTV solution from Quebec-based SmartSight. “We’ve tested the system, and it

works,” said Andy Bowman, a security integrator with SiteSecure Inc. of Sanford,

FL.

Velocity’s XML writer broadcasts data generated by the access control system to other systems, and the XML listener between Velocity and SmartSight will look for key triggers in the stream of day-to-day transactional data.

If an XML communication arrives from Velocity noting that input number one on panel number one indicates a forced door alarm, then a specific mini-program called a macro will be run. That macro executes particular commands or functions in the video system.

Each potential alarm reported by Velocity will have a predetermined macro executed by Smar tSight. Say camera number eight watches doors one, two, and three. When SmartSight discovers an alarm on door number one, it will pan, tilt and zoom camera number eight into its preset position for monitoring door number one, and it will put the image from camera number eight up on the alarm monitor in the security center.

While it is not new for one manufacturer’s access control system to communicate with another manufacturer’s video surveillance system, what is new is the ease and flexibility of the implementation when using Velocity’s XML output. It took very little time to write both a relatively simple XML listener—to identify and translate the security system trigger events into a command for the target system—and the additional macros that perform the desired video system controls.

In the old days, one could have achieved such interoperability by hardwiring potentially thousands of access control relays to video system inputs or under taking a massive software integration development project to create a custom, code-level integration of the products (which, by the way, would need to be updated every time any of the vendors came out with new product versions). Both alternatives are vastly more complex, time consuming and costly than XML-based interoperability.

Other building systems can be made to interoperate as well, said Bowman. For instance, if a facility were concerned about the possibility of an attack on the air handling system, intrusion alarms might be placed on secure doors protecting the HVAC ducts. Should one of those alarms go off, the HVAC controller, programmed to listen to access control data, would hear an XML phrase about the forced door. In turn, the HVAC controller would shut down the air handler to eliminate the possibility of an airborne contaminant spreading through the facility.

If You Can’t Fly, You Can’t Work Here

XML isn’t necessarily the best tool for all security interoperability

assignments. Sometimes it is preferable to use an application programming

interface (API).

At the Palm Springs International Airport in Palm Springs, CA, an API now handles the labor-intensive job of checking government-issued no-fly watch lists against airport employee rosters.

Federal laws designed to combat terrorism require airport security to check all airport employees against the watch lists, the same lists used to check out airline passengers and crews. These lists contain thousands of names.

“Every time we process a new employee, we have to make sure he or she isn’t on a watch list,” said Shawn Flinn, airport operations supervisor at Palm Springs International. “And we have to recheck all employees’ names each time an updated watch list arrives. In those cases, we have to compare the entire new list to our entire employee database. It was very time consuming to do it manually.”

Looking for a way to automate the checks, Flinn inquired if the airport’s access control software, a Hirsch Velocity system, could handle the job. After all, every airport employee’s name resides in the security system. Could Velocity compare its database of employee names with the names in the watch list database?

[an error occurred while processing this directive] “It was a perfect job for our API,” said Mark Allen, manager of Hirsch’s Professional Ser vices Group. Allen’s group wrote a database-matching program that sits between Velocity’s API and the watch list files, and installed it on an airport workstation. Now, to check airport employees against the watch lists, Flinn simply drags the watch list database into the API’s inbox folder. The program runs a comparison at a certain time every day and whenever a new list comes in. “It looks in the inbox, pulls out each watch list name, and runs it against the names in Velocity,” Flinn said. “Then it generates a report with any matches.

“It takes 30 seconds to run all the names on the lists. Before we got the API, it took 30 seconds to check a single name. It really speeds the process.”

Tell the Technology to Handle It

It’s clear interoperability not only saves time and money, it automates

routines and solves problems that couldn’t be solved otherwise. A non-security

system can listen to all the security system events and transactions, identify a

key event, and then do literally hundreds of things with that information,

depending on the customer’s needs. It can post information to a website page,

control cameras, change recording modes, fire relays, turn on microphones, dial

phones, send pages, play recorded messages over the audio system, and run macros

and other programs that initiate even more actions.

While many implementations involve a non-security system responding to a security system event, interoperability works both ways. Authorized third-party systems can also send commands to the security system. For instance, the data on a newly hired employee can flow automatically from the human resources system to not only the physical security system for instant credentialing and door access, but also to the IT system for instant assignment of network log-on rights and permissions.

XML- and API-enabled security systems have already begun to replace less advanced security systems that can’t talk or listen to other systems or that require the complex code-level integration approach. It’s not hard to see why both end users and integrators are enthused: low project cost, quick and easy implementation, measurable financial benefits, and intriguing application possibilities—quite an exciting combination.

About the Author

Scott Howell is manager of worldwide marketing for Hirsch Electronics, where he directs the global advertising, trade shows, lead management, telemarketing and Web initiatives. Mr. Howell can be reached at: marketing@hirschelectronics.com

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

[Click Banner To Learn More]

[Home Page] [The Automator] [About] [Subscribe ] [Contact Us]