“Control” must be the fundamental goal.

January 2011 |

[an error occurred while processing this directive] |

|

Back to Basics

“Control” must be the fundamental goal. |

|

| Articles |

| Interviews |

| Releases |

| New Products |

| Reviews |

| [an error occurred while processing this directive] |

| Editorial |

| Events |

| Sponsors |

| Site Search |

| Newsletters |

| [an error occurred while processing this directive] |

| Archives |

| Past Issues |

| Home |

| Editors |

| eDucation |

| [an error occurred while processing this directive] |

| Training |

| Links |

| Software |

| Subscribe |

| [an error occurred while processing this directive] |

PID

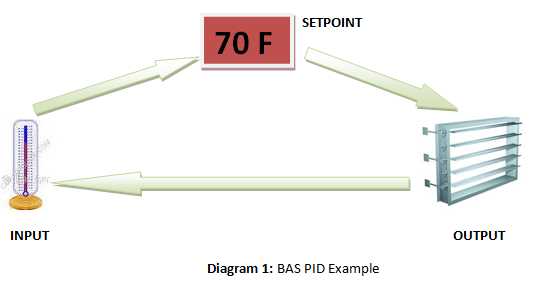

The fundamental goal is to control an input at a desired set point by

manipulating an output. We must not forget this fact. The goal is

starting to get lost behind the great technological advancements such as open

protocols, web and IP integration. “Control” must be the fundamental

goal. Without control, technological advancements are

useless. The history of control theory goes back over 100

of years to Proportional, Integral, Derivate (PID) control theory. The

PID theory is the fundamental control strategy used in the BAS industry and

we are not putting in enough time to understand the concepts and to apply

theory to reality. Incorrect PID settings can cause a system to

hunt if setpoints are exceeded by outputs reacting too aggressively,

causing increase in energy consumption and mechanical equipment

failures. In a recent survey many experienced BAS

engineers could not explain the exact theory behind the PID

algorithm.

The PID

controller is a feedback controller which calculates error, which is

the difference between the input and the desired set point. The goal is to

minimize the error by adjusting an output. For example in building

automation as depicted in diagram 1, the input is the temperature sensor,

the set point is the desired value of the room temperature and the output is a

damper which allows air flow. Therefore to minimize the error between

the actual temperature and set point, the amount of air flow is

adjusted via damper.

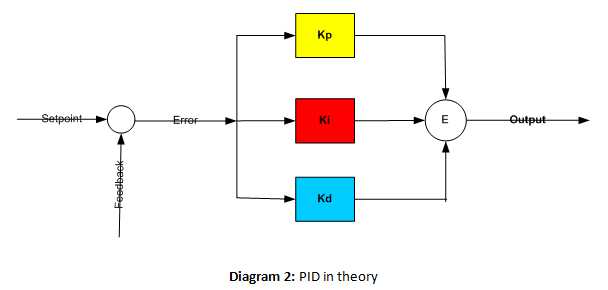

How do we maintain this dynamic system? It is achieved by setting the

correct factors for the proportional (P), Integral (I) and Derivative

(D) coefficients.

Proportional (P):

The proportional term makes a change to the output that is proportional

to the current error value. Therefore a large proportional

increases the output by that factor causing instability, if only

proportional is used.

Integral(I): The integral term is proportional to both the magnitude of the error and duration of the error. Therefore summing the instantaneous error over time gives the accumulated error that should have been corrected previously. This sum of error is multiplied by the integral factor to obtain the output. It accelerates the input towards the set point.

Derivative (D):

The derivative term calculates the rate of change of error and this is

multiplied by the derivative factor to the output. The derivative term

slows the rate of change of the controller output. It is used to reduce

the overshoot caused by the integral component and improve stability of

the output.

The goal of control is to tune the PID parameters to correct values to control the dynamic system in a stable manner.

We have a mathematical formula, but why do we keep failing to obtain optimal control parameters?

Trial and Error:

Tuning PID parameters is a trial and error procedure. To truly tune a

system, the engineer must tune the parameters with minimum, maximum and

normal system operation and observe the output over a time period. It is

not as simple as entering a value. This process is neglected by many

engineers due to time pressures in the project.

Vendor Definition:

PID is a generic algorithm for control and the P, I and D factors are

just coefficients. Therefore different vendors have different meanings

for these factors. Some treat it just as a factor; others treat it in

time scale. Therefore if a system is tuned using certain PID parameters

in one BAS system, the same parameters most likely fail in

another system. PID parameters used in one BAS system can not

used in another system.

[an error occurred while processing this directive]Continuous Tuning:

Tuning a PID to correct values at the start of a project is not enough.

During building life cycle maintenance, it must be reviewed as the

dynamics of the system can change. However, this is not a standard

practice in our industry. Generally the PID values are set by the engineers

at the start of the project and those values remain there for life. We are

continuously deriving strategies to save energy in buildings. Many

dollars are spent on new research to develop theories and to retrofit

buildings. It can be argued that with simple retuning of PID values it

can save substantial amounts of energy without the need to spend

millions of dollars. For example; a recent energy audit on a

government building proposed a change of pulsed based heating valves to

analog based valves to improve energy performance. However the root

cause of the energy increase was not the pulse based valves, but the

tuning of the PID algorithm. It was originally tuned based on the

analog valves causing the system to only perform full heating or no

heating. Therefore with a simple change of PID values, system stability

was achieved with substantial energy

savings.

Copy and Paste Technology: A common engineering principle is to reuse good solutions. Do not reinvent the wheel. In order to use this principle the user must understand how and why the original solution is a good solution; not just copy and paste the solution. This copy and paste phenomenon is used commonly in the BAS industry but not correctly. Many BAS solutions are copied from past projects without really understanding what is being copied. Five years ago many copied solutions went unnoticed as the equipment being automated was the standard fan coil units, air handlers, chillers and boilers. Even a slight variance was unnoticed as it did not affect the end customer. However, now with the evolution of energy management concepts many buildings are using new strategies such as chiller beams to cool buildings, weather stations, window control, rain water harvesting etc… Therefore the older solutions developed 5-10 years ago are out of date and will not operate efficiently in this environment. The new specifications are more stringent in terms of error to reduce energy consumption, therefore even a PID parameter to control a basic fan coil unit must be reviewed. Therefore do not just copy and paste solutions without knowing what you are copying. Time is precious, however with a wrong solution at the start of the project, you will spend lot more time throughout the life cycle of the building fixing the defects.

It is

very easy to get caught up in the BAS technological advancements.

However we must remember to do the basics properly, to benefit from the

technology.

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

[Click Banner To Learn More]

[Home Page] [The Automator] [About] [Subscribe ] [Contact Us]